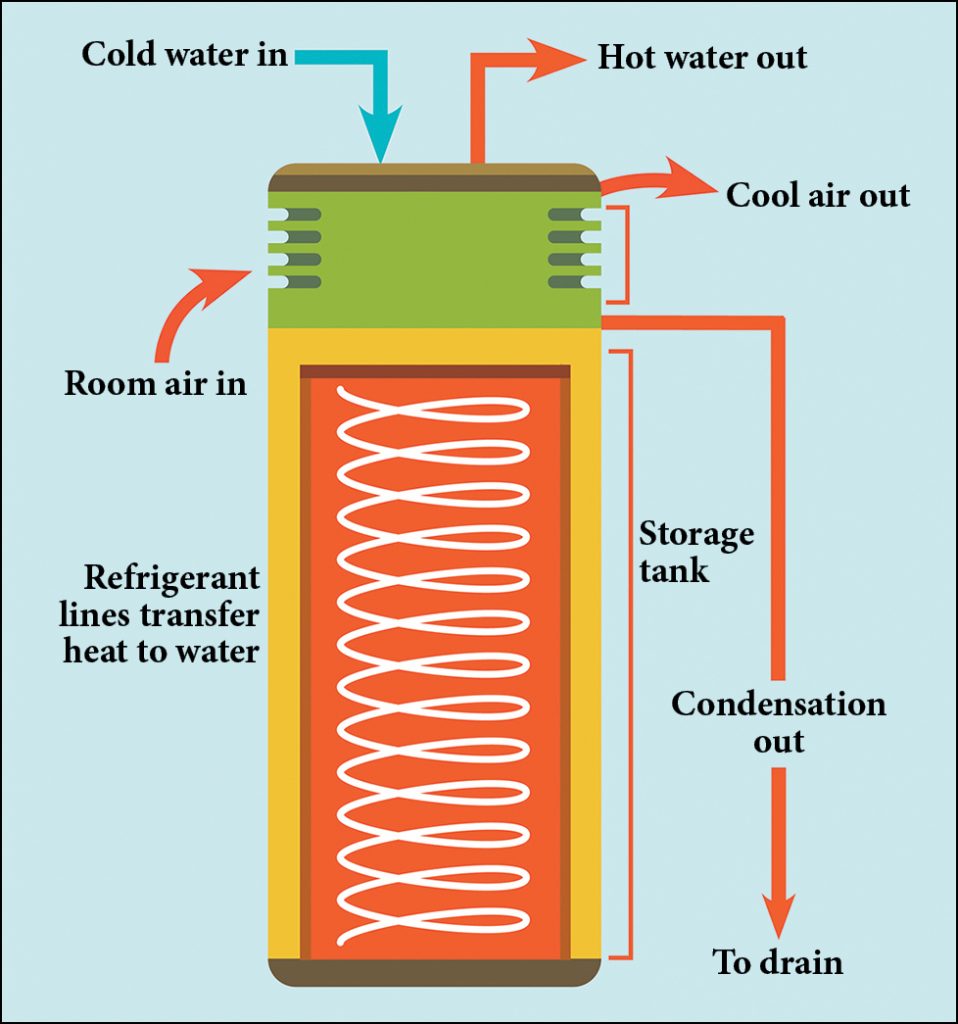

A heat pump water heater works by pulling heat from the surrounding air and transferring it to the water in its storage tank. Source: Portland General Electric (portlandgeneral.com)

The contractor remodeling James Tuleya’s house on the Peninsula a few years ago was surprised to find an uncommon type of water heater awaiting installation. Tuleya had taken advantage of a PG&E rebate program to purchase an electric heat pump water heater instead of a gas-fueled one. An energy efficiency expert and board chair of Carbon Free Silicon Valley, Tuleya was a pioneer in a shift which is about to change homes throughout the region, boosted by recent climate protection grants from the Bay Area Air Quality Management District.

This summer, the Air District awarded a total of $4.5 million to public agencies across the region for projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions. According to Abby Young, planning and climate protection manager at the Air District, the aim of the grants is to create models that can be scaled. “The biggest contribution the district can make is creating the examples that can be exported outside the Bay Area. We are looking for replicability and scalability,” she commented.

Carbon Free Silicon Valley strongly encouraged community choice aggregator Silicon Valley Clean Energy (SVCE) to apply for a climate protection grant to fund a heat pump water heater incentive program. Carbon Free Silicon Valley is a climate advocacy umbrella organization for multiple Carbon Free groups in Santa Clara and San Mateo counties. These groups supported formation of the community choice aggregators which now supply clean energy to the Peninsula and San Jose. Once the aggregators went online, the Carbon Free groups turned to the next step: how to use the clean energy more effectively. They found inspiration in a presentation by Pierre Delforge of the Natural Resources Defense Council, who showed them the results of a 2016 study for UC Berkeley’s CoolClimate Network on residential sources of greenhouse gas in the Bay Area. Evaluating energy use in homes across the region, and factoring in progress in reducing the carbon footprint of electricity by methods such as community choice, the study suggested that reducing natural gas use in buildings was the next problem to solve.

About 85 percent of natural gas in Bay Area homes is used to heat water or heat living spaces. Not only is electric heat pump technology available to perform both of those functions, it can do them more efficiently. Using the same technique that moves warm air from inside a refrigerator to the outside, heat pumps can move warmer air from outside a water heater to heat the water stored inside. Because the pump is just moving heat, not creating it, the appliance can be exceptionally more energy-efficient than burning natural gas to get the heat.

Heat pumps are more widely used in other parts of the country than in California, for several reasons. One is that natural gas was historically cheaper here than electricity, although rates are beginning to change. Also, a more temperate climate means less demand for energy-saving ways to heat water or rooms, or for air conditioning, another heat pump application. However, less extreme temperatures mean heat pumps don’t work as hard to get results. Jennifer West, program manager at Alameda County’s StopWaste, noted, “With our climate, this is a technology that should be used more.”

Unfamiliarity with heat pump appliances other than refrigerators and air conditioners has also been a barrier. As John Supp, account services manager at SVCE, explained, “If the buyer doesn’t know about it, they won’t demand it. If the supplier doesn’t know about it or have it in stock, that makes it harder for the buyer. And it’s been much harder for a developer to do this, because it’s something unusual for permitting agencies, and that means it takes more attention and therefore more time to process the permit.”

Of the 17 climate protection grant applications that the Air District funded, the three largest were for projects to support expanded use of heat pump water heaters. “These were larger because [the recipients] are all coordinating and working together on incentives,” Young noted. The largest grant, in the amount of $400,000, went to BayREN, a regional energy efficiency group, and will be administered by StopWaste. The agencies will collaborate to address the market supply piece of the heat pump water heater problem.

“We’re working on incentives for the distributor network, influencing the people who will be trusted to make recommendations to a buyer on what to get,” commented West. “We aren’t giving out money,” she added. The community aggregators, and municipal and local power companies, will be providing the funding. BayREN is also planning contractor trainings, with the goal of increasing both the numbers and geographical spread of knowledgeable installers, and will distribute information on heat pump water heaters to industries that provide solar installations and electric vehicles to help reach consumers interested in further electrification of their homes.

The Air District awarded $325,000 to SVCE; the aggregator will match that for a total of $650,000 for its program. It plans to take the heat pump water heater message to consumer groups that may be particularly receptive, such as Tuleya’s Carbon Free group and residents already considering remodeling.

Both Tuleya and Supp described some of the barriers to adopting the new technology, and SVCE is earmarking approximately $5,000 per home to overcome these and move a consumer closer to total electrification. To start with, electric heat pump water heaters are more expensive than gas water heaters. In addition, gas water heaters are often installed in a small space; to gather enough warmer air to efficiently function, heat pumps need either more space, such as a garage, or more ventilation. Finally, electric heat pump water heaters need a 220-volt outlet, and this may involve upgrading a home’s electrical panel and running additional conduit and wiring.

SVCE’s financial incentives will make the cost to the consumer a few hundred dollars less than putting in a new gas water heater, and they will have an upgraded electrical panel that will support further electrification of their home with an electric vehicle charger or an induction stove. Tuleya strongly supports this approach; although he upgraded his water heater, he still doesn’t have the circuits he would need for an all-electric home. His advice? “Don’t think of just one device at a time — for some people, even with a higher up-front cost, heat pump water heaters will pay off over time, but in combination with electric vehicles and solar panels, the cost easily evens out, because an electric vehicle can save $20,000 over 20 years.”

Supp mentioned that SVCE will acquire data from monitoring actual usage patterns of electricity by homes with the new water heaters. This will enable them to design programs for better time-of-use charges to lower consumer costs. “Maybe after you take your hot shower early in the morning, you can wait to heat more water until there’s plentiful solar energy later in the day,” Supp suggested. SVCE also expects to contribute anonymized data to regional and state partners for large-scale energy efficiency planning.

The City of San Jose, which operates the San Jose Clean Energy aggregator, also received a $325,000 award. San Jose spokesperson Jennie Loft wrote, “We will be leveraging this award with the same amount by providing outreach and education, including to low-income households in San Jose. Nearly all of the funds are slated to go towards … financial incentives for San Jose residents to change out their natural gas water heater for a heat pump water heater.” San Jose recently adopted a climate action plan, and has a zero-net-carbon demonstration that will tour the city to let residents try out electrification.

Other climate protection grants included $296,997 to Marin County for decarbonizing buildings, including adoption of heat pump technology, and $296,220 for the City of Palo Alto Utilities’ efforts to replace gas wall furnaces in multifamily buildings with heat pumps. Although new construction will be required to accommodate heat pump appliances starting in 2019, Young stressed, “The goal is getting natural gas out of our buildings, and the challenge is with the buildings we’ve already built.”

Leslie Stewart covers air quality and energy for the Monitor.