Horned Grebe dining on a polychaete worm (Alitta sp.) offshore from the Candlestick Point State Recreation Area. Polychaete worms are part of the benthic macroinvertebrate community that can be affected by dredging activity. (Photo by Raul Agrait, iNaturalist.org)

As I lifted my paddle out of the water near Brooks Island Regional Reserve, I looked up and saw a giant metal claw emerge from the water’s surface and deposit a sizable slurry of slick and shiny mud in a large flat barge. My mind boggled as to the kinds of life one would see in the muddy load as it poured out of the claw. As I continued paddling by I also wondered about what kinds of pollutants might be hidden in the growing pile of sediment as the metal claw brought up its next load.

While covering a large area, San Francisco Bay is on average less than three meters deep at low tide, so navigation channels, ports, harbors, and marinas are dredged on a regular basis to maintain the Bay as a major maritime hub. In fact, approximately 3 million cubic yards of materials are dredged annually from the Bay.

Because the Bay is the largest Pacific estuary in the Americas and home to numerous endangered species and delicate habitats, it is certainly worthwhile to explore how dredging is done in the Bay and what kinds of ecological effects there are.

Retrieving the sediment from the Bay’s floor is done by using either mechanical dredge heads, such as a clamshell or excavator, or hydraulic dredge, such as a hopper dredge. Mechanical dredging meticulously lifts sediment up by the bucketful and therefore takes longer and is more expensive.

Clamshell dredging project in the Delta. Photo: Ellen Johnck, Lind Marine

In contrast, hydraulic dredging takes up sediment and water somewhat indiscriminately, “just imagine it’s kind of like a vacuum cleaner underwater,” shares Brenda Goeden, the Sediment Program Manager at San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC).

Hydraulic dredging is limited in the Bay because of its high impacts. ”Most of the dredging that happens in San Francisco Bay is a mechanical dredge because of entrainment issues,” said Goeden.

Entrainment is the inadvertent removal of organisms during hydraulic dredging suction. “It’s sucking up not only sediments but sucking in water at the same time, and the water has plankton in it, it has fish eggs in it, and it has invertebrates, and fish.”

Environmental work windows exist to encourage projects to dredge when special status species are not present, such as during late fall and winter when Pacific herring are not spawning and migrating salmon and steelhead are present.

“Some fish will, when there’s a disturbance, leave the area. And other fish, like flat fish and sturgeon will hunker down into the sediment,” said Goeden. “So their behavior creates a little bit more of a problem for them. But the idea is that dredging would happen at the time of year when they’re least likely to be affected.”

Further, dredging projects must also provide a 45 meter buffer from the nearest eelgrass populations, with the eelgrass buffer increasing to 250 meters where suspended sediment is expected while dredging. Buffers are also required when dredging near other sensitive species, such as endangered Ridgway’s and Black Rails.

Dredge operating at the entrance to the Richmond harbor. Photo: Viktoria Kuehn, San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission

Sediment is precious stuff

Sediment in San Francisco Bay flows from the Sierra Nevada through the San Joaquin and Sacramento Valleys and finally through the Delta into the Bay. Hydraulic mining during the Gold Rush caused large pulses of sediment inputs between 1849 and 1919, with flows increasing by about 9 times compared to estimated pre-Gold rush levels.

Sediment loads flowing into the Bay have been decreasing since 1999. Even less sediment is expected to flow from the Delta as the climate warms and water demands increase. This decrease in sediment inputs can mean less need for dredging, but it also means a reduced ability for our tidal wetlands to keep up with sea level rise.

Beneficial reuse of dredged sediments is a key strategy for ensuring valuable sediment stays within the larger Bay ecosystem. Reuse options include being deposited in tidal wetland restoration sites, lining landfills, or shoring up levees.

The addition of sediments to tidal wetlands raises the elevation, enabling vegetation to colonize and subsequently serve as a buffer to sea level rise for surrounding communities and prevent further erosion.

Sediments earmarked for dredging are tested for dozens of chemical and metal contaminants. “What the testing tells you is what the quality of the sediment is. And then from there we make a determination on where the sediment can go, either being disposed of or used in beneficial reuse,” says Goeden. “On average, less than 5% of sediments dredged annually are not appropriate for beneficial reuse.”

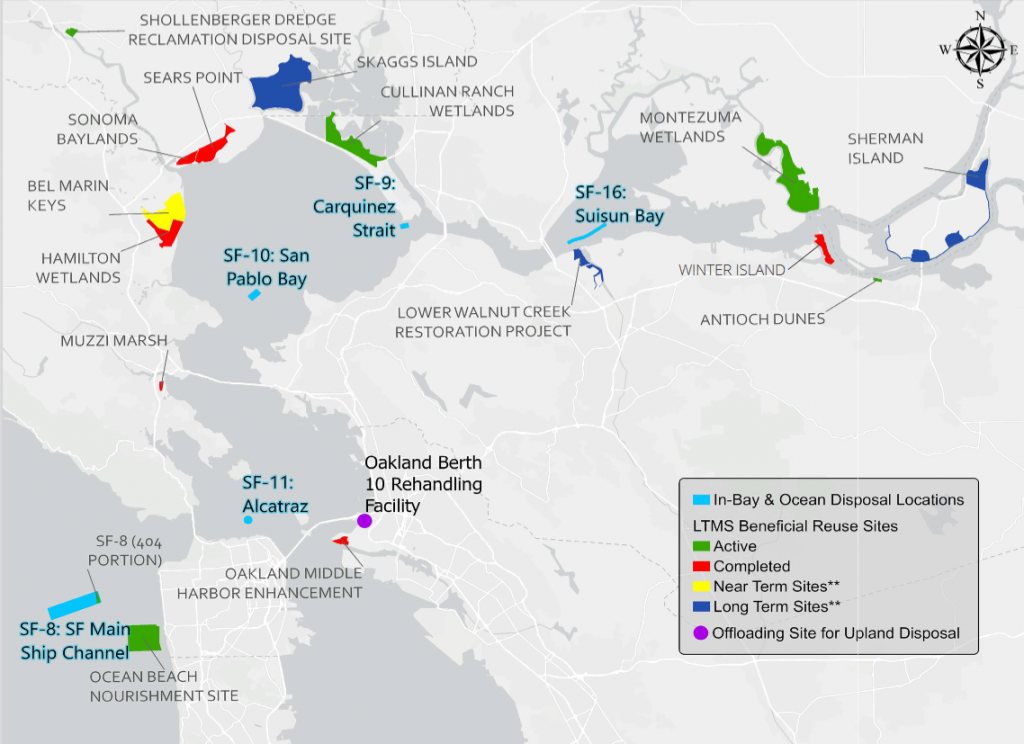

As of 2019, over 25 million cubic yards of dredged sediment have been used to restore over 7,500 acres of wetlands, including Sonoma Baylands, Hamilton Wetlands, Bair Island, and the currently active sites, Cullinan Ranch and Montezuma Wetlands.

However, even though sediments can be reused does not mean they are. “The challenge is the cost and people’s willingness to go to beneficial reuse,” said Goeden. “The [dredging] contractor would have to take into account the time, the distance traveled, and the diesel” to transport the sediment to the reuse site.

For their projects, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers requires contractors to provide bids to use the sediments for beneficial reuse but federal law mandates the beneficial reuse option must be the least costly one if they are to select it.

Materials that are not designated for beneficial reuse and are not more toxic than established toxicity thresholds are eligible to be deposited in the Bay. In-Bay deposition sites include Suisun Bay, Carquinez Strait, San Pablo Bay, and near Alcatraz Island.

More toxic sediment is deposited at offshore sites, including the San Francisco Bar Site west of Ocean Beach and the San Francisco Deep Ocean Disposal Site (SFDODS) located 55 nautical miles west of the Golden Gate Bridge just off the continental shelf.

Map of deposition and beneficial reuse sites for material dredged from the San Francisco Bay. From San Francisco Bay’s Dredger Handbook.

In only a few instances exceedingly toxic sediments are deposited in various upland facilities and landfills where toxins can be managed safely. “It’s not at all a significant amount of dredging sediment that’s held up by contamination. It’s pretty rare at this point,” said Goeden.

Disturbance and recovery

Dredging is a localized disturbance that alters the benthic environment and the surrounding water column. San Francisco Bay’s benthic habitat is comprised of sediment that is a varied mix of silt, sand, and gravel and is home to a diverse community of macroinvertebrates, including polychaetes, oligochaete, bivalves, gastropods, and crustaceans such as crabs, shrimp, isopods, and amphipods.

“The invertebrates are important because they are part of the ecosystem,” said Goeden. “They have a value in their own right but they are also fish food and food for higher order animals like mammals and birds. So when you’re removing invertebrates in the sediment you’re removing a food source.”

Many species of fish dine on these sedimentary denizens. Bottom-dwelling skates, leopard sharks, green sturgeon, and halibut favor macroinvertebrates when young, preferring fish as they can swim farther afield as adults.

Pelagic fish found in the water column, like Pacific herring and northern anchovy, have both particulate feeding, where they take a bite out of their prey, and filter feeding, where tiny plankton and other food particles are strained through filaments in their gill rakers. These fish, as well as young smelt and rockfish, forage on invertebrates found on the Bay floor.

According to a 2017 report on the effects of dredging on macroinvertebrate communities in San Francisco Bay by researchers with the U.S. Geological Survey, two major effects of dredging are localized turbidity and the displacement of the macroinvertebrate community.

Turbidity, or sediment plumes, stresses both the invertebrates and the fish species looking for them. “The presence of sediments in the water is along the lines of, for us, if the air is smoky it’s harder to breathe,” Goeden explains. “We have responses such as coughing or having a harder time getting the air we need to breathe. Similarly for fish you can have clogging of gills, coughing, difficulty with just breathing in that circumstance.”

After an area is dredged and invertebrates are removed, they repopulate the dredged area over time in a process known as succession, with “pioneer” species appearing first. These early arrivals facilitate the environmental conditions for longer-lived species that follow by altering nutrient availability through feeding and burrowing activities.

Succession occurs in practically all kinds of habitats after a disturbance — think landslides, fires, glacial retreat — and the order that types of species that appear after a disturbance are often predictable. Even brushing your teeth restarts predictable and (hopefully regular) successional sequence of microorganisms in the biofilm on your teeth and gums.

The USGS researchers found it can take about three years for the species richness and biomass of the macroinvertebrate community to reestablish. Later successional species are those that can burrow deeper in the sediment and are longer-lived.

How soon the organism populates the dredged area depends on how mobile their larvae are and how far away from the dredged area the larvae had to travel. The less mobile larvae, such as polychaetes, that are farther away from the dredged area are less likely to populate the dredged area than more mobile species like clams and crabs, whose larvae spend time floating in the water column.

There is no doubt that dredging impacts the Bay’s aquatic ecosystem, but it is also an important part of our region’s commerce and recreation. Dozens of people in multiple government agencies strive to ensure dredging projects are completed mindfully, to minimize impacts on the delicate balance of our underwater communities that often remain unseen.

To learn more about sediment budgets in San Francisco Bay, see the article “Where’s the Dirt?” published in the Bay Area Monitor in 2017 by Robin Meadows.

Interested readers can refer to the San Francisco Bay Dredger’s Handbook for more information about maintenance dredging in San Francisco Bay.