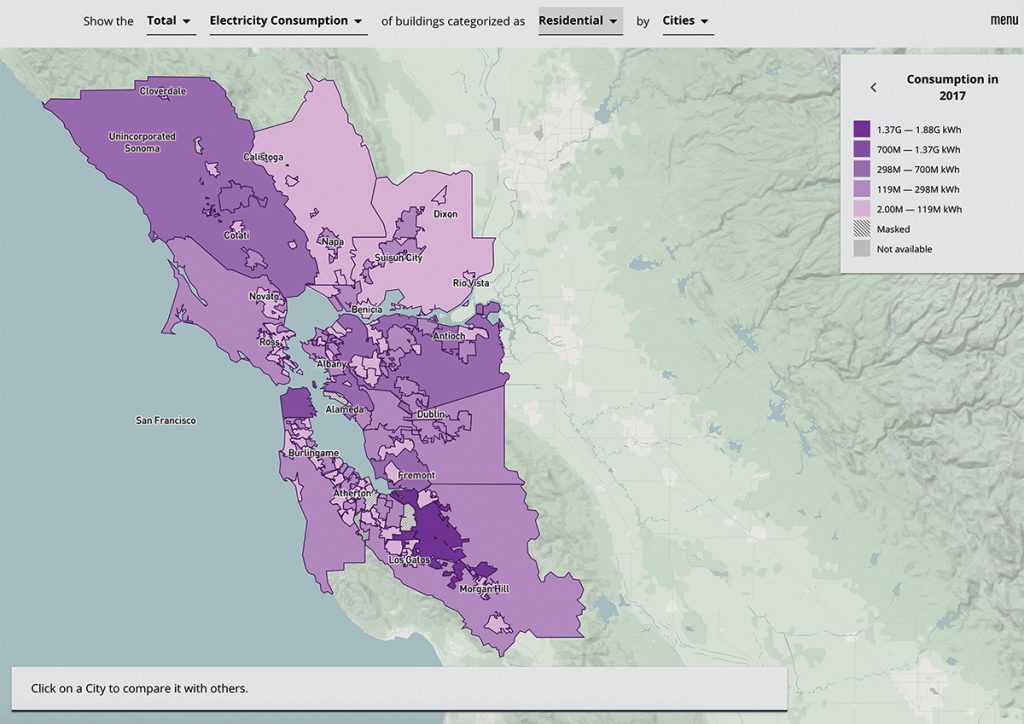

The BayREN Energy Atlas allows online users to view energy consumption as data visualization maps. Screenshot from bayarea.energyatlas.ucla.edu.

Many Bay Area residents are addressing climate change by altering their purchasing habits, driving electric vehicles, and replacing natural gas appliances in homes. More are needed, though. “Early adopters” are important to get trends started — they pilot the techniques and model them for others — but it takes more than early adopters to make changes on a scale that will really move the needle. Unfortunately, those who would benefit most are sometimes unable to join in at all.

According to the BayREN Energy Atlas, a database tool developed by the California Center for Sustainable Communities at UCLA, households in disadvantaged communities lag behind more affluent areas in adopting rooftop solar panels and electric vehicles. Some of these communities also show indications of lower energy use than is optimal for comfort and health, which UCLA researchers attribute to under-utilization of heat or air-conditioning due to the cost of paying for utilities. Nationwide, low-income families spend 20 percent of their monthly income on energy, compared to 3.5 percent in other households, according to the Green & Healthy Homes Initiative, a nonprofit which works to advance equity through safe and energy-efficient housing.

Low-income residents have been left out of the movement toward greater energy efficiency in several ways. People living in disadvantaged communities may not be included when energy efficiency programs are designed. They may not take advantage of incentive programs due to limited time, a mistrust of government agencies, or difficulties in accessing online opportunities. They may be unaware of changes they could make, or are unable to make such changes because they lack the resources or don’t own the property where they live. For example, a family in a rented unit may have no opportunity to switch to solar power, even though that would save on their electricity bill each month. There may be no money for insulation that would bring that bill down while keeping them more comfortable.

This is doubly unfortunate because often the impact of missing out on new technologies to improve energy efficiency affects more than finances. Health may also suffer, especially respiratory health, which is often linked to heart problems. Asthma, prevalent in disadvantaged communities, can be triggered by fumes from gas stoves or by smoke from wildfires or neighborhood fireplaces drawn into poorly-sealed homes.

In hot weather, homes without air-conditioning can create heat-stress illnesses for residents, particularly the elderly. Michael Kent of the Contra Costa Health Services Department addressed this issue during a November forum held by BayREN, an Association of Bay Area Governments program focusing on regional efforts to save energy. Kent noted that in Contra Costa, with the exception of the affluent retirement community of Rossmoor, a map of heat vulnerabilities lines up neatly with disadvantaged communities.

The result is that many residents spend more money to live in conditions that are less comfortable, less healthy, and more damaging to the environment. Weatherization programs are an excellent starting point for many households to reduce this burden; adding insulation and sealing cracks can lead to immediate improvements, making heating and cooling more effective at a lower cost.

Utility bill assistance programs are often a gateway to accessing weatherization programs. This is one of the ways the nonprofit Community Action Marin assists low-income and underserved residents in Marin County; as part of its Safety Net Program, it distributes the county’s LIHEAP (Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program) federal funding to help residents with unmanageable energy bills. Safety Net Services Director Laurel Hill told the BayREN forum audience that assistance for some rural residences may entail more than paying a bill. “If they’re heating with wood, we tell them, ‘We can get you a cord of wood’.” With partner agency MCE Healthy Homes, Community Action Marin then works with residents to reduce future bills, through energy audits and referrals to a weatherization program provided by a second partner agency, San Francisco Peninsula Energy Services.

Hill noted that eligibility for Marin’s energy assistance is based on the income of the resident, not that of landlords. However, landlords must consent to any property changes; some are reluctant to participate in the weatherization program, so it has been under-utilized.

The health benefits of weatherization are the focus of the Contra Costa County Asthma Initiative. In its pilot project, the asthma initiative trained home health nurses to evaluate weatherization needs in the households of patients who had recently visited an emergency room for asthma problems; research has shown that asthma is correlated with both lower income levels and heat vulnerabilities. Kent then helped those households to apply to weatherization programs funded by LIHEAP and by state cap-and-trade funds earmarked for disadvantaged communities. As Kent described it, “The goal is to use preventive measures to save money on emergency room visits and hospitalizations.” While helping the medical system cut expenditures, these measures also ease residential utility bills and reduce additional health episodes for asthma patients.

Home weatherization and electrification can help residents save money on utilities while also addressing asthma problems. Photo by Alec MacDonald.

The asthma initiative has recently received a three-year grant from the California Department of Health Services through the Sierra Health Foundation to do 150 in-home asthma assessments. As needed, households will be provided with asthma prevention modifications and supplies, and also matched up with weatherization programs. A one-year grant from the Bay Area Air Quality Management District will fund data collection and management, and will also cover electrification upgrades — such as range hoods or central air filtration — for approximately 38 of the first 50 households in order to improve indoor air quality and reduce greenhouse gases.

Electrification — moving to electric appliances powered by renewable energy — is the next step after weatherization, particularly for asthma patients, as fumes from natural gas heaters and stoves are often not vented adequately and are even more likely to create indoor air problems if a home is no longer drafty. The BayREN Home+ program provides rebates and other incentives to homeowners and landlords to encourage them to upgrade to more energy-efficient electric heating, air-conditioning, and appliances.

Kent said that the money part of the asthma initiative has been complicated. One problem has been “siloed” funding, with eligibility requirements and covered programs differing by funder. For example, if a leaky roof is creating mold problems that exacerbate asthma, money from a weatherization program may not be sufficient, and if the project isn’t eligible for a program for disadvantaged communities, that leaves a gap between need and solution. Grants are also not a long-term, stable basis for a program that needs to serve far more than a few hundred households.

The Contra Costa program has encountered the same reluctance by landlords to participate as in Marin. Kent mentioned an Antioch resident who needed to get air-conditioning following a hospitalization for heat sickness. Without insulation, new air-conditioning would be extremely expensive to maintain. However, insulation could not be installed without a wiring upgrade, which the landlord was unwilling to complete.

Landlords’ decisions are also a constraint on overcoming disparities in use of solar energy. The California Center for Sustainable Communities at UCLA has faced this on a project to get a low-income community to net-zero energy use by creating a community solar facility, among other strategies. Eric Fournier, research director at the Center, explained to BayREN forum participants, “You have the issue of ‘agency’ — renters are not in control of many of the housing factors, such as retrofits, solar, and battery storage.”

Residents are not always ready to change, either. The Center began with building community awareness of the advantages to making the changes, such as comfort, lower bills, and better air quality. Fournier stressed that it’s also important to build trust, whether by promising and delivering local jobs as part of the project, or speaking the language of the people who will benefit.

A growing number of programs are available to improve energy efficiency in communities that have been lagging in participation. Elemental Accelerator, with a base in East Palo Alto, invests in nonprofits working on equity-building projects, including solar energy, in “frontline communities” — the predominantly low-income and minority communities with pollution burdens that feel the impacts of climate change first. GRID, a national nonprofit, installs solar projects, including battery storage, that serve low-income households and communities. The accomplishments of all of these programs will benefit both individuals and the environment.

Leslie Stewart covers air quality and energy for the Monitor.