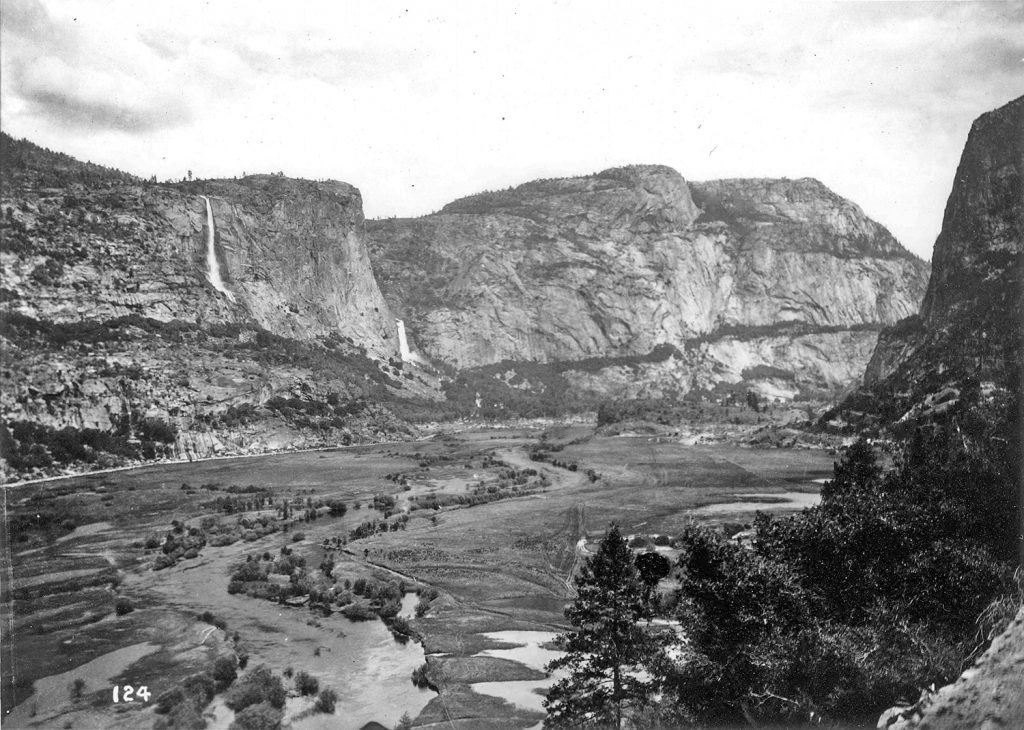

This photo from the early 1900s shows Hetch Hetchy Valley from the southwestern end, with the Tuolumne River flowing through the lower portion of the valley prior to damming. Photo by Isaiah West Taber.

When Spreck Rosekrans visits Hetch Hetchy — the valley in Yosemite National Park that San Francisco turned into a reservoir nearly a century ago — he looks beyond what is. Instead, he envisions what once was and could be again. “I imagine a meadow, dotted with oak, pine, and fir trees, and with the Tuolumne River meandering through it,” said Rosekrans, executive director of Restore Hetch Hetchy, a Berkeley-based nonprofit.

Hetch Hetchy is just 15 miles north of Yosemite Valley and the two are often called twins. Historical photographs show why: like Yosemite Valley, Hetch Hetchy has sheer granite walls that originally rose dramatically from a wide valley floor. Today, however, that valley is under 300 feet of water.

Building a dam on the Tuolumne River at Hetch Hetchy was fiercely debated when it was proposed in the early 1900s, and the reservoir continues to spark controversy today. The latest twist in this long story has just unfolded, and the final chapter is yet to come.

The Sierra Club is one of the original opponents of flooding Hetch Hetchy, calling it “the greatest blemish in our national parks,” and the organization’s former executive director David Brower recommended that Rosekrans lead an effort to restore the valley. Rosekrans had previously worked at the Environmental Defense Fund, a New York-based environmental advocacy nonprofit, where he was lead author of the 2004 report Paradise Regained: Solutions for Restoring Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy Valley.

In 2015, Restore Hetch Hetchy filed a lawsuit against the City and County of San Francisco, seeking a ruling that Hetch Hetchy Reservoir violated California law. “The state constitution says all water use must be ‘reasonable,’” Rosekrans said. “We argued that the reservoir is not reasonable because the value of the restored valley is greater than the cost of changing the water system.” At the time, they put the recreational value of the restoration at up to $8.8 billion and the cost of water system changes at $2 billion, both over 50 years.

The trial court ruled in San Francisco’s favor in 2016, saying that California courts lack jurisdiction over Hetch Hetchy because the dam there was approved by Congress. So Restore Hetch Hetchy filed an appeal with the Court of Appeals in Fresno, which heard arguments from both sides in May of this year.

Supporters of the appeal include Barbara Griffin and Robert Binnewies, both former superintendents of Yosemite National Park. In a brief filed with the appellate court, they said, “The trial court did not determine that the continued use of the dam and reservoir was ‘reasonable’ — rather, it concluded that the question could not be examined at all.” In other words, they say the trial court did not address the substance of Restore Hetch Hetchy’s argument.

Other supporters of the appeal include the State Water Resources Control Board. That said, the board does not support either side in the Hetch Hetchy debate. Rather, in a brief submitted to the appellate court by California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, the board said that the trial court “erred” when it ruled that federal law preempted California water law.

The Fresno appellate court disagreed. In July of this year, the judges affirmed the previous ruling in favor of San Francisco: “The trial court correctly concluded Restore Hetch Hetchy’s claims are preempted under federal law.”

Legal issues aside, is it theoretically possible to change the Hetch Hetchy water system? Jay Lund, director of the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences, thinks so. The Hetch Hetchy water system includes other reservoirs, and the one in Hetch Hetchy Valley stores only about a quarter of the water San Francisco gets from the Tuolumne River.

In a 2006 analysis in the Journal of the American Water Resources Association, Lund identified additional options for storing the water that is currently in Hetch Hetchy Reservoir. But changing the system would be jaw-droppingly expensive. “Hetch Hetchy would never get built today, but restoring it is something for the long haul,” Lund told the Monitor.

Steve Ritchie, a San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC) water manager who oversees the Hetch Hetchy system, says storing the water elsewhere would cost billions of dollars. “The notion that we could restore Hetch Hetchy would be very attractive if it didn’t have any other effects — but it does,” Ritchie said, adding that the water goes to about one third of the people in the Bay Area. “It’s not just San Francisco.”

Some of the costs would be operational, recurring year after year. That’s because Hetch Hetchy Reservoir has built-in advantages that save huge amounts of money. For example, thanks to the reservoir’s nearly 4,000-foot elevation in the Sierra Nevada, the water in it is amazingly pure.

“Hetch Hetchy captures snowmelt that runs off granite,” Ritchie said. “It’s very clean; there’s very little sediment.” The water is disinfected with ultraviolet light but, in contrast to almost all other reservoirs in the U.S., filtration is not required. Lund estimates that being able to forego filtration saves the SFPUC $1 or $2 billion every year.

Restoring Hetch Hetchy could also come at an environmental cost. “I would never put Hetch Hetchy where it is, but the fix itself would be destructive somewhere else,” said Laura Tam, sustainable development policy director of SPUR, a San Francisco-based nonprofit dedicated to urban planning in the Bay Area. For example, raising a dam on another reservoir in the system could flood another stretch of the Tuolumne River that, while outside Yosemite National Park, is designated as a national Wild and Scenic River.

For Restore Hetch Hetchy, however, the overriding concern is righting what they see as a historical wrong to an iconic national park. “We are fighting a battle to try our case in the California courts,” Rosekrans said. “Next we’ll ask for a review from the state Supreme Court.”

Robin Meadows covers water for the Monitor.