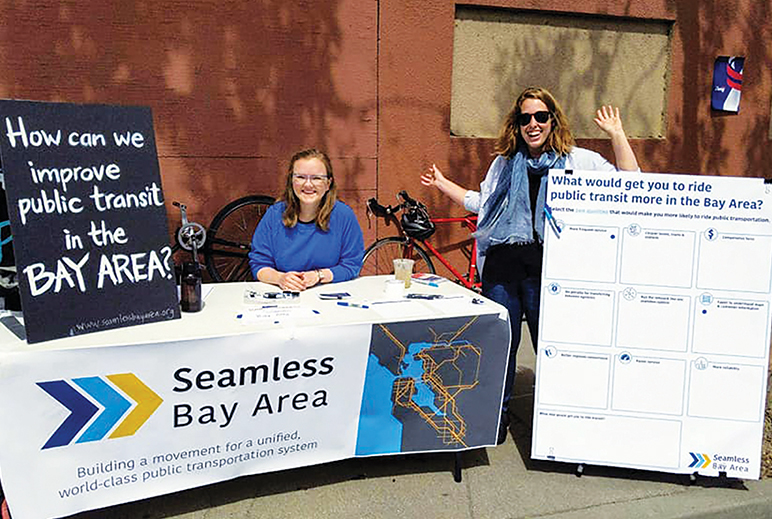

Stakeholders in regional transportation operations such as the grassroots group Seamless Bay Area are calling for transit fare policy reform. Photo courtesy Seamless Bay Area.

What if it were possible to travel by bus, train, electric bike, or rideshare using a single account to pay for these transportation costs?

It’s one of several fare policy strategies suggested to help prioritize rider and regional needs in Solving the Bay Area’s Fare Policy Problem, a report published in May by the civic planning organization SPUR. Fare policy sums up the rules that define how much people pay to use public transit, a tab riders increasingly scrutinize with the introduction of new mobility options like Uber.

The root of the transit fare problem is a jumble of fare structures, passes, and prices that are set and managed by more than two dozen individual agencies, according to the report. This arrangement creates rider confusion and compromises quality and equitable access, outcomes that limit public transit’s promise to connect people.

For example, there are nine different local bus fares on Clipper, the region’s transit fare payment system, ranging from $1.50 to $2.50, as well as multiple discount rates for youth and seniors. Overall, Clipper relies on 19,463 fare policy business rules to run the entire system.

But Clipper’s makeover — it’s in the process of being upgraded to become a more flexible, account-based payment system — offers a chance to reduce complexities and streamline fare policy, said Arielle Fleisher, SPUR’s senior transportation policy associate and report author. Clipper was launched in 2010, replacing the previous TransLink system.

Bay Area transit advocates and officials considered fare integration around the time Clipper launched, but the idea never fully developed. Fare integration raises concern because it could spell losses for some operators heavily reliant on fare-box revenue.

For a better sense of the Bay Area’s current situation, SPUR’s new report outlined five problems resulting from a “disjointed” fare approach. Disparate policies limit transit use, penalize people who take multi-operator trips, and price out low-income riders who can’t afford the high up-front cost of a monthly pass.

Another issue is that a lack of multi-operator fare policies limit state and Bay Area plans for integrated transit stations and services. Lastly, transit riders are shying away from Clipper because they don’t understand what it supports and offers, whether it calculates transfers and discounts, if it works across systems, and whether it holds cash in addition to transit passes, according to the report. This hurts Clipper’s appeal.

“We have this growing body of evidence to maximize Clipper 2.0,” Fleisher said. “It’s important that we don’t miss the opportunity.”

New willingness to entertain fare policy reform is becoming evident. Three separate ideas surrounding an integrated transit fare system were among the finalists in a public transportation planning competition held last year by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) and the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG). The competition called for participants to conceive bold “transformative projects” exceeding $1 billion, as part of the agencies’ Horizon planning initiative exploring opportunities and challenges the nine-county region may face by 2050.

SPUR was one of the competition finalists who proposed an integrated transit fare system; the other two came from the organization Seamless Bay Area and from a two-person team of college student Eddy Ionescu and local transportation planner Jason Lee. Seamless Bay Area’s proposal called for fare, service, and branding integration. SPUR urged a “fare by distance” model where prices vary based on the journey’s starting and end point. In their transportation network blueprint Move Bay Area, Ionescu and Lee proposed a course of action that preserves an agency’s ability to set fares and institutes a regional transfer policy.

Those ideas were added as a single collective project to the list of 12 competition finalists slated for further analysis. They joined an inventory of 82 other potential new transportation projects. Depending on how all the projects stack up, they might be included in Plan Bay Area 2050, the region’s blueprint for transportation and land-use planning, scheduled for adoption in 2021.

Disparate fares, if not addressed, will continue to dissuade people from using more than one transit service. They also will motivate people to drive, adding to traffic congestion, pollution, and carbon emissions. Cars aren’t public transit’s only competition either. The rise of Uber and other new mobility services can be, in some cases, more direct and cheaper than using two or three transit services whose fares are not integrated.

“People are more sensitive to the cost of public transit because they have more options,” said Ian Griffiths, co-founder and director of Seamless Bay Area. The two-year-old group has been campaigning for a unified regional transit network.

The future of fare policy topped an MTC fare integration seminar in February that was attended by board members, staff from transit agencies, and advocates. The seminar included a presentation about Metrolinx, a transit agency serving the Greater Toronto and Hamilton area, and the steps it’s taken to assess fare integration and the effects on revenue and ridership.

One idea born from the seminar was the creation of a steering committee to guide fare integration work if transit agency leaders choose to examine the business case for the concept. This would entail a robust analysis of the costs, benefits, and impacts of fare integration from multiple perspectives, with the goal of helping agency leaders understand the various tradeoffs involved.

MTC staff expect to give a detailed update on fare integration at the June 17 Clipper executive board meeting, said William Bacon, policy and financial analyst at MTC. If needed, MTC has identified approximately $600,000 in Regional Measure 2 funds that could support work on the business case.

Jeanne Mariani-Belding, communications and marketing manager for Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit (SMART), said, “We are very interested at SMART in being part of that conversation and we’ll be following the issue closely.”

In the meantime, SPUR’s report lays bare the many challenges before regional transit agencies and policymakers. In addition to agreeing on a vision for coordinated fare payment, there also needs to be a clear understanding of costs and benefits. SPUR recommended the business case examine two different scenarios. The first is a revenue-neutral setup to increase ridership overall, which would boost profits for the entire system that could be distributed among operators via revenue sharing.

The second is a revenue-investment scenario where a certain amount is tucked away, either by the region, state, or both, to support integrated fare structure development.

“We’re not in a position to absorb a loss in revenue,” said BART spokesperson Jim Allison. “We’re in a tight budget squeeze for the next couple years.”

Well beyond fiscal matters, there is an urgent need for someone or some agency to champion the entire effort. MTC, Clipper’s executive board, transit operators and their boards, and the California State Transportation Agency will need to think about shifting practices and roles, and even assuming new responsibilities, according to the SPUR report.

SPUR’s report covers a lot of ground, discussing the nuances of strategies and action plans for policymakers, transit operators, and advocates to fit all the fare policy pieces together.

Should all of this move forward, SPUR’s vision of a single-payment system would mean riders could seamlessly pay for different expenses — buses, trains, e-scooters, ride shares, bridge tolls, and parking. It also would ensure riders with low-incomes qualify for reduced fares and incentivize customers with promo codes and discounts that can be shared across programs faster.

When a transportation system is “cost-effective, easy to use, and frequent enough to provide a faster journey, that’s a potentially transformative impact that really changes the value prop of public transportation,” Griffiths said.

Cecily O’Connor covers transportation for the Monitor.