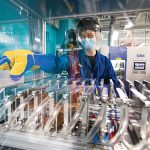

Seawalls like this one on the San Francisco shoreline (photographed in 2016) receive a great deal of impact from waves. New research suggests that such structures create a bounce-back effect, amplifying tides elsewhere along the bay. Photo by Dave R/Flickr.

As shoreline communities in the San Francisco Bay Area scramble to prepare for rising seas, they should also be mindful that protecting themselves could worsen flooding elsewhere. This is because seawalls can reflect and amplify tides. “Decisions in one location could affect hazards in another,” said environmental engineer Michelle Hummel, who began studying the bay while at UC Berkeley and is now at the University of Texas at Arlington. Her latest research reveals that building seawalls along relatively small sections of shore could raise water levels enough to have far reaching effects, even all the way across the bay.

“It was pretty surprising,” Hummel said of her findings, which she and co-author Mark Stacey of UC Berkeley reported in the February 2021 issue of the journal JGR Oceans. “We had seen it for seawalls at the county level but didn’t expect small-scale projects to have bay-wide impacts.”

Hummel and Stacey combined a model of tides in the San Francisco Bay with projections for sea-level rise, and found that seawalls could amplify the tide by up to four inches. “That might not seem like a lot — but if you also have a king tide, storm surge, or high wind, that could extend the amount of flooding,” Hummel explained.

Seawalls’ effects on water level varied with the landscape of the shoreline. The impact was minimal along the steep bluffs of headlands, which dominate the shore in Marin County, San Francisco, Point Richmond, and the Carquinez Strait that runs between Contra Costa and Solano counties. This makes sense, Hummel pointed out, because a bluff is much like a seawall, so building seawalls along headlands wouldn’t do much to change the way water behaves in the bay.

But building seawalls in other places could, especially in the wide alluvial valleys where rivers flow into the bay. “Wide alluvial valleys have more area for storing water, so protecting and cutting them off from the bay would mean higher water levels in the bay,” Hummel says. The impact of seawalls on water levels was most pronounced in the alluvial valleys where the Napa and Petaluma rivers join San Pablo Bay, and where Coyote Creek joins the South Bay. “Seawalls there can cause cross-bay interactions,” she continued, “especially at the Napa River, where protections can increase water levels as far away as the South Bay.” In other words, when incoming tides hit a seawall at one end of the bay, they can bounce back and ultimately make the water higher at the other end.

These findings add urgency to Bay Adapt, a new effort to coordinate protections against rising tides in the bay. “We need to act more regionally,” said project leader Jessica Fain, who directs planning at the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC). “It can’t be city by city — one city shouldn’t make flooding in another one worse.” Launched in 2020, Bay Adapt aims to facilitate consensus on a regional vision for sea-level rise preparation in the bay. “Then local plans can be consistent with the whole,” Fain said. Other advantages of a common vision include technical assistance for local planners, who are often spread thin, as well as advocating with a more unified voice for resources from the state.

Fain acknowledges that finding a common voice for the hundreds of diverse stakeholders in Bay Adapt — from elected officials to business interests to environmental groups to community organizations — is an ambitious goal. But she’s inspired by a similar effort at the tip of Florida, where four counties joined forces a decade ago to coordinate on climate change. If they can do it there, surely we can do it here too.

Indeed, California is beginning to move in this direction. In a 2020 report called What Threat Does Sea-Level Rise Pose to California?, the Legislative Analyst’s Office said regional coordination on sea-level rise preparation should be one of our priorities as a state, and held up Bay Adapt as an example. In addition, last year State Senator Toni Atkins of San Diego introduced Senate Bill 1, which calls for more cooperation in coastal planning and development.

Here in the Bay Area, hot-button issues for reaching consensus on sea-level rise adaptation include whether to require regional planning or to encourage it with incentives, a choice that Fain refers to as the stick versus the carrot. Moreover, sea-level rise preparations are much farther along in some parts of the Bay Area than in others, raising environmental justice and equity issues. “We don’t want to hold back early movers but we also want to think long term,” Fain said. “We want to support vulnerable communities.”

One of the most vulnerable is East Palo Alto. This low-lying city of about 30,000 is on the edge of the bay in San Mateo County, which is predominantly white and among the top ten wealthiest counties nationwide. In contrast, East Palo Alto is far more diverse, with mostly people of color — Latinx, Black, Asian, and Pacific Islander — and far less affluent, with 13 percent in poverty.

East Palo Alto sits right between two of the earliest sea-level rise adaptation projects in the Bay Area. Just 12 miles to the north, construction has begun to raise the levee that runs all along the water side of Foster City, a town of 34,000. The project is funded by Measure P, a $90 million bond Foster City voters overwhelmingly passed in 2018, and is scheduled for completion in 2023.

And just 13 miles to the south of East Palo Alto, plans are well underway to build a new levee in Alviso, a San Jose neighborhood at the tip of the South Bay. The project, which will also restore tidal marsh, is estimated at nearly $200 million. Funding to date includes a federal contribution of $80 million, and local contributions of about $60 million from Measure AA, the 2016 Bay Area-wide parcel tax, as well as $17 million from Santa Clara County’s Measure S, a 2020 parcel tax. Construction on the Alviso levee project is expected to begin this year and completion is scheduled for 2028.

There’s no doubt that Foster City and Alviso both need to bolster their levees against sea-level rise. But, as environmental engineer Hummel’s work shows, such unilateral actions could come at the cost of harming unprotected communities like East Palo Alto. “The Bay Area needs a cohesive plan for equity, instead of letting everyone do their own thing,” Hummel said.

BCDC’s Bay Adapt helps give East Palo Alto and other vulnerable communities a voice at the regional level. “We’re at the forefront of sea-level rise,” said Julio Garcia, who is program director for Nuestra Casa, an East Palo Alto community organization dedicated in part to environmental justice. “In about twenty years, a lot of our community will flood.”

Garcia is also part of Bay Adapt’s 32-member Leadership Advisory Group and, after years of outside planners and engineers parachuting in to East Palo Alto with top-down fixes, he welcomes the move toward including local residents in decision making from the outset. “We live right here — we know where it floods and what will be good for our community,” he said. “Maybe we don’t want to see a barrier like a seawall, maybe we want a more natural barrier like restored marshland.”

Putting local people at the heart of making decisions that affect them will promote trust and buy-in when it comes to sea-level rise adaptation. “Creating true partnerships with communities is a step up from just coming in and being experts,” Garcia said. “It will be great for everybody to have a common plan to tackle these issues.”

Robin Meadows covers water for the Monitor.