Debbie Viess mushroom hunting at Mt. Shasta. Credit David Rust

Debbie Viess is dreaming of morels, delicate wild mushrooms that pop up as the cool of winter yields to the warmth of spring. Her favorite recipe for morels when they’re tiny and tender is with fresh spring peas in cream sauce over pasta. “They’re delicious,” she says.

If you don’t know what you’re doing, however, this meal could also be dangerous. Mushrooms are notoriously difficult to identify and some are poisonous. For instance, novices can easily mistake false morels (Gyromitra esculenta) for true morels. “The look-alike Gyromitra species can be seriously toxic,” cautions the morel page of the Bay Area Mycological Society, which Viess co-founded with David Rust, her husband and fellow mushroom enthusiast.

The mushroom world is small but intense. “It’s an obsessive hobby,” Viess says. Egos can get in the way of the parts she prizes — the thrill of the hunt, the satisfaction of identification, and the wonder of the natural world — and her club welcomes mushroom lovers at all levels from beginner to expert.

There’s a lot for mushroomers to love here. The Bay Area is a biodiversity hotspot and fungi are no exception. “We have an explosion of mushrooms in the fall about two weeks after the first soaking rain,” Viess says.

Before the pandemic, the Bay Area Mycological Society met at UC Berkeley and Viess hopes to resume these get-togethers this fall. “We’re open to the public and have really wonderful mycologists,” she says. “You can ask questions and bring mushrooms for identification.” UC Berkeley journalism professor Michael Pollan attended while researching his book The Omnivore’s Dilemma, which features a meal he made from foraged mushrooms and other ingredients gathered in the wild or grown at home.

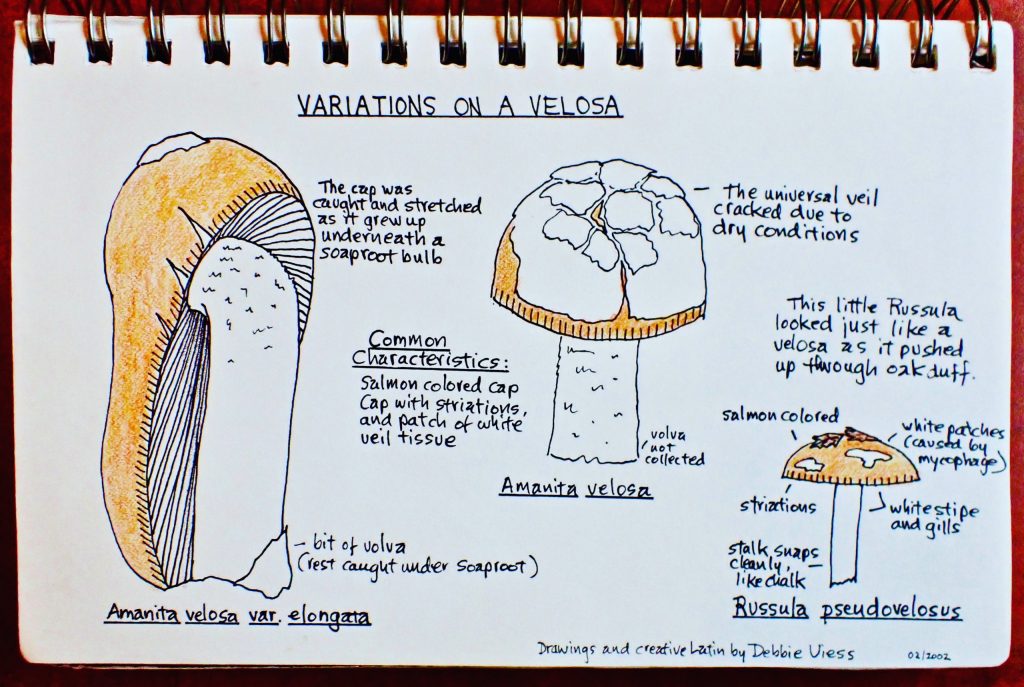

A sketch from one of Viess’ many field notebooks.

Learning from experts is imperative for beginners. “Identification is very complicated,” Viess says. “People see what they want to see, finding places where descriptions overlap and ignoring those where they don’t — you need to show what you find to a knowledgeable person when you’re just starting out.”

Viess is an expert on Amanita mushrooms, which include edible as well as lethal species. Two of the latter grow in the Bay Area: the Death Cap (Amanita phalloides) and the Destroying Angel (Amanita ocreata). Both grow under oaks and their bland looks belie their toxicity.

In one of her proudest moments, Viess published a rebuttal to famed fungi expert David Arora, who encouraged eating Amanita muscaria. Graced with a white-dotted red cap, this mushroom is inebriating but also neurotoxic. “He was the god of mushrooms and he said ‘everybody go eat Amanita muscaria,'” she says. “You can boil out the toxins but people shouldn’t be encouraged to — the procedure to make muscaria wholly non-toxic is complicated.” Failure to follow the procedure exactly has resulted in nausea, vomiting and deep amnesiac sleep.

Despite their differences, Viess still recommends Arora’s All That the Rain Promises and More: A Hip Pocket Guide to Western Mushrooms for those just getting started in mushrooming. There’s just one caveat. The book was published in 1991 and the names of many mushrooms have changed since then, as mycologists have incorporated genetic analysis into species designations.

Viess shares her expertise in mushroom safety widely. People bring her mushrooms to identify in person, and veterinarians call for help when dogs eat wild mushrooms. She was also invited to serve as an Amanita expert in the public Facebook Group Poisons Help; Emergency Identification For Mushrooms & Plants. “It includes ace identifiers from all over the world,” she says. “It’s nice to give back, to have an arcane skill that can help people.”