Bird’s Eye View: Science from the Sky

Despite the rising popularity of drones, open spaces haven’t welcomed them with open arms. While the Federal Aviation Administration regulates the national airspace, concerns about privacy, safety, and wildlife disturbances have led many public land authorities to restrict unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) on their grounds. Ironically, the remote-control machines that are the bane of nature lovers can be a boon for land management and conservation.

Perhaps better known for military applications, UAVs can also help scientists gather images, environmental samples, and other data. In the Bay Area, these machines have proven useful for monitoring invasive plants, tracking restoration projects, and surveying wildlife. With high-resolution mapping capabilities, the devices have even played a role in restoring public access to places where the machines will never be allowed for recreational flying.

“Drones create a dual concern,” said Marc Landgraf, the external affairs manager for the Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority. “Our mission is to give people a peaceful experience on our lands, but we also want to further scientific research within our open space preserves. So we don’t have an outright ban on drones. We have a permitting process that would allow the responsible use of UAVs for conservation research and law enforcement.”

The darker side of drone use has been spotlighted in reports of UAVs surveilling people, provoking eagles into attacking them, and starting fires with crash landings (as happened last year in Sunnyvale’s Baylands Park). Fortunately, there aren’t a lot of those incidents, said Lance Brede, a police lieutenant and watch commander for the East Bay Regional Park District. “We’ve had a ‘no model aircraft policy’ for years, so most situations are the result of people who simply aren’t aware that UAVs aren’t allowed,” he said.

Drones can also pose risks to other aircraft. Last year a California Highway Patrol helicopter in Martinez had a close call when a student flew a drone within feet of its windshield. A brand new study claims birds are far more likely than drones to collide with planes, but as Brede noted, “A two-pound bird can go through a windshield like a missile. Imagine what a 50-pound drone could do.”

In research, though, UAVs offer an enticing way to efficiently and cost-effectively gather data. Beyond the high-profile studies that use drones to hunt for poachers in Africa or track illegal logging in the Amazon, many Bay Area scientists have tested how the machines perform on a variety of environmental projects.

In Tomales Bay, for example, scientists tried out unmanned aircraft systems for the mid-winter waterfowl survey. Conducted for more than 50 years, this survey uses piloted aircraft to fly transects across Tomales Bay and much of the San Francisco Bay, as well as regional sloughs, salt ponds, and marshes. The flights take several days and the accompanying ground counts take a couple of weeks, explained Orien Richmond, a biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. In collaboration with several other agencies, they found that UAVs provided high-resolution images for bird counts and identified species without unduly disturbing the birds.

“It’s really challenging for biologists in a plane to get accurate bird counts,” said Richmond. “They only have a couple of seconds to look down and estimate numbers and there might be multiple species in one area. Why risk putting biologists in the air, when unmanned systems could potentially get better data, more safely?” he asked. The danger is real — aviation accidents account for two-thirds of job-related deaths among wildlife biologists, according to one study.

UAV counts can be extremely precise, according to a just-released study by Australian researchers. Published in Scientific Reports, the researchers compared UAV-derived counts with those made at the same time by on-the-ground census takers for colonies of frigate birds, terns, and penguins. Moreover, the remote-control machines can survey hard-to-reach populations and places.

The U.S. Geological Survey has also used UAVs to count colonies of white pelicans in Nevada, estimate tule elk populations on the Carrizo Plain, and search for abandoned solid waste in the Mojave Desert.

One caveat to using drones in bird surveys — or any wildlife work — is to avoid disturbing the animals, particularly during breeding season. It isn’t only the startling sounds the UAVs make. Sometimes the shape of the machine mimics a predator. “That’s something recreational drone users may not be aware of,” noted Richmond. “For some birds — particularly sensitive colonial nesting species — individuals may abandon their nests following a disturbance, which can negatively impact populations.”

“It’s important to separate recreational drones from research use,” emphasized Sharon Dulava, a Humboldt State University master’s degree candidate who took part in the Tomales Bay bird survey. “Research projects are carefully planned to minimize those sorts of impacts. There are so many types of projects where UAVs could be safer, more cost effective, and less stressful for wildlife while we acquire valuable information. So we need to keep the door open [for research drones].”

One of the biggest limitations to research drones — aside from navigating the permit process for permission to fly — are the short flight times dictated by limits to the vehicle’s power supply. The Tomales Bay study drones only had enough power to fly for about 40 minutes, while a regular, piloted plane could go at least four hours before refueling.

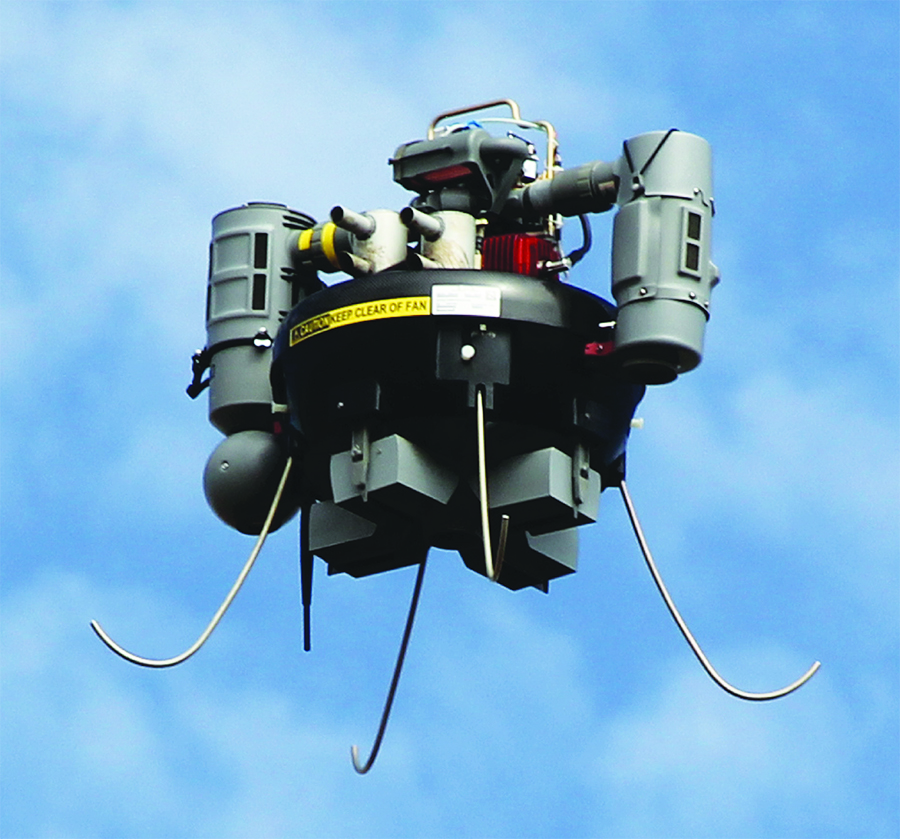

Another design constraint involves making machines that can carry big “payloads” (such as fancy cameras) yet retain maneuverability and lower body weights. And many of the less expensive machines are downright noisy. But it seems only a matter of time before Silicon Valley technology can solve these performance issues.

Sean Headrick, the man behind the San Carlos-based company AeroTestra, is working to optimize drone designs for research. He views the flying machines as collection devices that operate similarly to scanners, gathering visual data from the world that can then be processed by computers. Most of his projects involve mapping. With photogrammetric software tools, the two-dimensional images gathered by his unmanned machines are translated into richly detailed 3-D maps.

“For a fraction of the cost of a manned aerial survey, we can use UAVs to map on the ground with centimeters of resolution,” said Headrick. These high-resolution methods helped make the topographical maps needed by the Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District to plan for opening parts of Mount Umunhum for public use this fall.

Some companies, such as the San Francisco-based Airware, sell only software that researchers can customize for particular projects (like tracking rhinos in Africa). Others, like GeoWing, headquartered in Oakland, focus on mapping services that may use drones or manned aircraft to get the job done. “Drones can be great tools to cost-effectively monitor change over time,” said Jeffrey Miller, the company’s vice president.

But, it isn’t all cameras and maps. As Headrick noted, the data gathering is only limited by the loads a UAV can carry. At the Blue Oak Ranch Reserve in San Jose, director Mike Hamilton outfitted drones to remotely sample ponds to analyze water quality and temperatures at various depths. These ponds are key habitats for tiger salamanders and western pond turtles. As methods are refined, data from the reserve could be compared with tests from ponds on grazing lands to assess the impact of cattle on water quality, for example. Other researchers have used unmanned aircraft to analyze particles in the Arctic atmosphere to help them better understand climate change.

“What we’re doing [with drones] related to conservation will allow us information that we could never have gathered any other way,” said Headrick. “And with an immediacy that we can do no other way, at a cost that’s so low there’s not a comparable thing out there.”

Elizabeth Devitt covers open space for the Monitor.