Governor Jerry Brown’s proposed 2017-18 state budget includes an expenditure plan for cap-and-trade auction proceeds, allocating more than $2 billion to a range of initiatives that reduce or sequester greenhouse gases. However, for the expenditure plan to move ahead, the governor’s budget first calls for a bolstering of the cap-and-trade program itself. Brown wants the legislature to confirm by a two-thirds vote that the agency in charge of the program — the California Air Resources Board — has the authority to administer the auctions beyond the year 2020. Extending cap-and-trade with supermajority approval would protect it from legal challenges, such as a current lawsuit from the California Chamber of Commerce claiming that the program imposes an unconstitutional tax on businesses.

The Third District Court of Appeal heard oral arguments in the lawsuit at the end of January, and has until late April to issue a verdict. However, both sides have affirmed they will take their case to the California Supreme Court in the event that they lose.

By raising doubts about cap-and-trade’s future, the lawsuit has likely had a chilling effect on the program’s quarterly auctions. The most recent one on February 22 garnered just $8 million, a sliver of the nearly $600 million that the state could have brought in by selling all available emissions allowances. The allowances — which are in essence permits to emit greenhouse gases — would seem to hold little value if cap-and-trade dissolves, so businesses have less incentive to purchase them until the program’s path forward becomes clearer.

Panelists (from left) Phoebe Seaton of the Leadership Counsel for Justice & Accountability, Amy Vanderwarker of the California Environmental Justice Alliance, Parin Shah of APEN, and Madeline Wander of USC in a workshop at Policy Insights 2017 in Sacramento.

Some environmentalists harbor their own skepticism about cap-and-trade, but for different reasons. These were on display at the nonprofit California Budget & Policy Center’s annual conference last Thursday during a workshop on climate change.

Panelist Parin Shah, a senior strategist for the Bay Area-based Asian Pacific Environmental Network (APEN), expressed concern that cap-and-trade’s auction system reduces nature down to a commodity.

“We are monetizing air,” he pointed out, encouraging the audience to “think about the moral implications of that.”

Morality aside, he contended that cap-and-trade is simply not that effective. He alluded to the relatively meager proceeds from the February auction, and argued that emissions-based taxation would generate a more stable revenue stream — that is, if policymakers must insist on pricing greenhouse gases. He offered several alternative examples which instead have been protecting the climate with regulatory mechanisms, such as through land use planning, vehicle emission standards, and requirements for investment in clean energy.

Shah went on to criticize cap-and-trade for failing to eliminate pollution hot spots, an idea elaborated upon by panelist Madeline Wander. The senior data analyst from the University of Southern California explained that many facilities which emit greenhouse gases simultaneously produce toxic co-pollutants such as particulate matter, imperiling the health of residents in nearby neighborhoods. Wander noted that these neighborhoods tend to house low-income people of color, who already suffer under numerous other disadvantages. She questioned cap-and-trade’s capacity to protect these vulnerable populations, citing her research team’s findings that many industry sectors have emitted a larger volume of localized greenhouse gases — and by correlation, more toxic co-pollutants — since the program took effect.

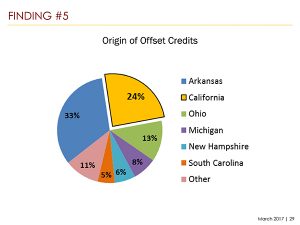

This uptick could have resulted from an improving economy (an interpretation voiced by one audience member), but the fact remains that industry facilities continue to threaten the health of California residents. And in an ironic twist, Wander revealed that many of cap-and-trade’s benefits occur out of state, through the program’s incorporation of offset projects. This means that, instead of purchasing emissions allowances, a business can comply with cap-and-trade requirements by investing in an offset project that reduces greenhouse gases — often involving forestry management, livestock biogas control, or the destruction of outmoded cooling equipment.

This slide from Madeline Wander’s presentation shows that the majority of cap-and-trade offset projects happen outside of California.

The Air Resources Board has sent no geographic restrictions on where these offset projects happen, and according to Wander, only 24 percent of them have been implemented in California.

She did provide a more favorable opinion about the way cap-and-trade revenue is being spent, noting 2012’s Senate Bill 535 (De León) requires certain percentages of that money go toward helping disadvantaged communities. The methodology for defining “disadvantaged” has been the subject of much debate, however, and Bay Area interests in particular have expressed dissatisfaction that funding criteria has shortchanged their region’s needs. These finer points may not matter very much, though, compared to the larger question of whether cap-and-trade can remain a viable program in the face of so many challenges. As the spring legislative season unfolds, stakeholders across the board will be watching and waiting for the answer.