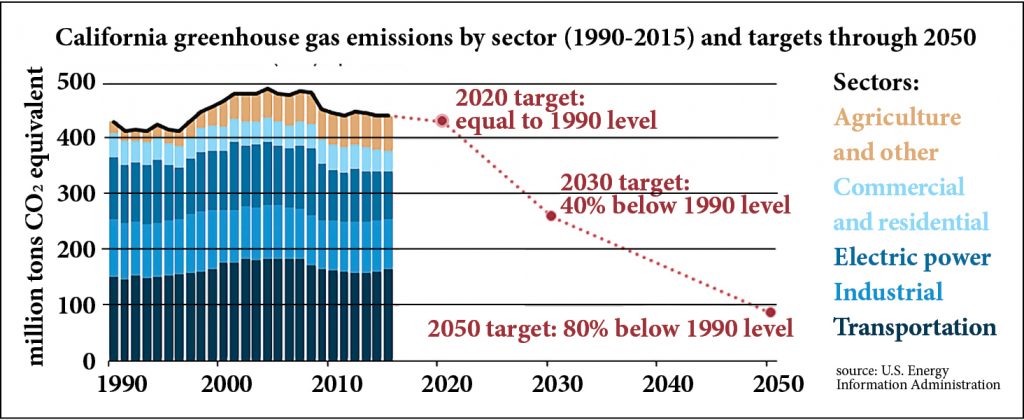

California intends to drastically cut greenhouse gas emissions in the coming decades.

Illustrations and comic strips from 1975, the year the Bay Area Monitor was first published, often depicted automobiles with little puffs of gray exhaust coming from their tailpipes. Refineries and factories were shown with tall chimneys emitting plumes of dark smoke. In the Bay Area today, these portrayals seem as dated as 1970s fashions and hairstyles. Few vehicles have visible exhaust, and industrial “smokestacks” normally emit only steam clouds.

Those changes are the result of policies and strategies designed and implemented over the past 45 years. As politicians, agency bureaucrats, and concerned residents worked incrementally toward changing air quality, it’s unlikely that they also foresaw just how different life would be in 2020 as a result. Electric vehicles, with charging stations in many locations? A stroll in a wildlife refuge next to a refinery, without watery eyes from pollution? Homes, schools, and public facilities generating their own energy from solar panels?

What might be different about the Bay Area in 45 years, if today’s plans continue to move forward? The results may not be so easy to notice — screens don’t become brighter when TVs run on solar power, and flowers don’t grow six times bigger in cleaner air. How will people see tangible results as current programs reach their goals? Figuring this out can’t be done with any scientific certainty, but many groups around the region have plans that can suggest trends. From agencies to researchers to concerned residents, there is agreement that work needs to be done if 2065 is to be better than 2020.

In 2017, when the Bay Area Air Quality Management District adopted its current Clean Air Plan, the region was not fully compliant with state and federal standards for ozone, a key component in smog. Some communities were still experiencing localized impacts of particulate matter and toxic air contaminants. Since 2017, the region has faced two major smoke events from climate-change-enhanced wildfires.

By focusing on a “post-carbon year 2050,” the 2017 plan is addressing these concerns. It incorporates state air quality goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030, and 80 percent below 1990 levels by 2050 (see graph above). Strategies target ozone precursors, particulate matter, and toxic air contaminants as well as greenhouse gases.

As in the past, much of the plan involves incremental progress, using regulations and some incentive funding to decrease fossil fuel dependency, increase transit use, and control pollutants. New strategies involve green buildings, urban tree-planting, carbon sequestration in rangelands and wetlands, agricultural practices, and food waste disposal.

Jakub Zielkiewicz, advanced projects advisor with the Air District’s Climate Team, noted that some of the new strategies are aimed at creating behavior changes in the region.

“We looked at carbon emissions generated by Bay Area residents,” Zielkiewicz explained, “and we noticed that more than half of all emissions are driven by consumer choice and lifestyle. This includes emissions from the way we travel, and the food we eat — how are the goods we consume produced and processed? Where do they come from? For dairy and meat, for example, it’s not only the emissions associated with the processing and transportation of the final product, but also the methane emitted by the animals.”

As a trend toward the future, Zielkiewicz cited the Restore California Renewable Restaurants project, which adds a voluntary one percent surcharge to restaurant bills to supplement public funding for carbon sequestration programs such as carbon farming and compost application in agricultural operations and rangelands. Plan strategies and recent state legislation mean that all Bay Area residents will have food composting as part of waste management services within a few years.

For travel, together with a move to greater transit use, the increase in zero-emission vehicles will greatly improve air quality, although Zielkiewicz cautioned that tire and brake dust could still be problematic. Today, a big question is how to design vehicle charging infrastructure. In a glimpse of the future, Zielkiewicz mentioned that the Air District has funded chargers that are being installed on school properties. These could be made available to the public after school hours, which would benefit dense neighborhoods with multi-family buildings that may not have sufficient charging locations for everyone.

For a grassroots perspective, the Monitor also checked with two climate activists on how 2065 will be different. “What a question!” wrote Marti Roach, a member of Citizens Climate Lobby and 350 Contra Costa. “If we cannot dream about the positive results of a transition to a clean energy world, our efforts to mobilize toward it are much harder,” she added.

Berkeley energy-activist Eric Arens predicted that “the amount of fossil fuel burned will be low because it will be more expensive than solar and wind-generated energy.” This forecast is supported by multiple energy industry reports.

Along with renewables, Arens thinks vehicles and buildings will use hydrogen as fuel, writing, “Hydrogen will be made by electricity, which will be produced by solar panels and wind turbines. Many houses will have batteries or hydrogen-powered generators for use during high-rate time-of-use periods and during blackouts. The reason for using hydrogen is that it is much lighter than a battery that stores as much energy.”

Arens predicted that “small areas such as neighborhoods and towns will each be in a microgrid, that can be isolated from the large electric transmission lines. Each microgrid will have solar cells and batteries and hydrogen-powered generators that can provide at least some electricity to the microgrid. Utility outages will not cause total blackouts.”

Going even further, a recent article in Forbes predicted that energy from renewables will be efficiently managed throughout the day through remote adjustments to “smart” appliances such as heat pumps and refrigerators in thousands of buildings.

By 2065, residents will see the effects of bans on natural gas connections in new construction. Roach wrote, “Our electricity, which will be from renewable and clean energy sources, will power our buildings, making indoor air quality much higher. Recent studies have shown that leaking methane from gas in the home and workplace can contribute significantly to health problems like asthma.” Buildings without natural gas lines will also be safer in earthquakes.

Shifting from natural gas will have an additional side effect. Heat pumps provide air-conditioning as well as heat, and they don’t bring outside air into indoor spaces. In 2065, residents will be able to have cool filtered air, either in their own homes or in many public spaces, during excessive heat days caused by climate change, or smoke events resulting from wildland fires.

Arens had a question for the Monitor: “Will there be a typical Bay Area resident, or will there be more wealth inequality so that there will be wealthy residents and poor residents?” It’s an important consideration, since the region’s income disparity continues to grow. Some residents may still be living in spaces with obsolete natural-gas-powered appliances in neighborhoods endangered by old gas pipelines. They may use dirty fossil-fueled back-up generators if they are not connected to a reliable grid. Their homes may be inadequately protected from outdoor pollution, and they may lack access to adequate transit. Their neighborhoods may still have gas stations instead of clean vehicle charging facilities.

Zielkiewicz agreed that “the potential equity impacts could be significant” for some of the changes that are on the way. “We know that zero-emission vehicles are currently more expensive than gasoline-fueled cars, making their purchase more challenging from a financial perspective for lower-income communities,” he said, adding that the Air District is responding to the issue with programs such as Clean Cars for All, which assists with the cost of zero-emission vehicles. By 2065, there will be a substantially larger pool of used clean-air vehicles available as well.

While agency incentive programs will be extremely important to ensuring equity, Roach predicted more cohesive communities will address some needs. “The impacts of [weather] challenges on us will have stimulated greater community among folks as most people find themselves living in denser environments and there are many opportunities to help and be helped by others. Volunteers will help staff cooling centers or educate folks on growing food and ways to prepare for risks from heat, fires, and floods.”

Clearly, Roach is looking on the bright side, because climate change will not be completely reversed by what we are doing now. However, she concluded, “If we write the story the right way and stay the course on emissions reductions, with some help from sequestering more carbon from the air, we will be in a renaissance in 2065.”

Leslie Stewart covers air quality and energy for the Monitor.