Hot enough to fry an egg on the pavement? The pavement itself may be partially to blame — and the buildings around it as well.

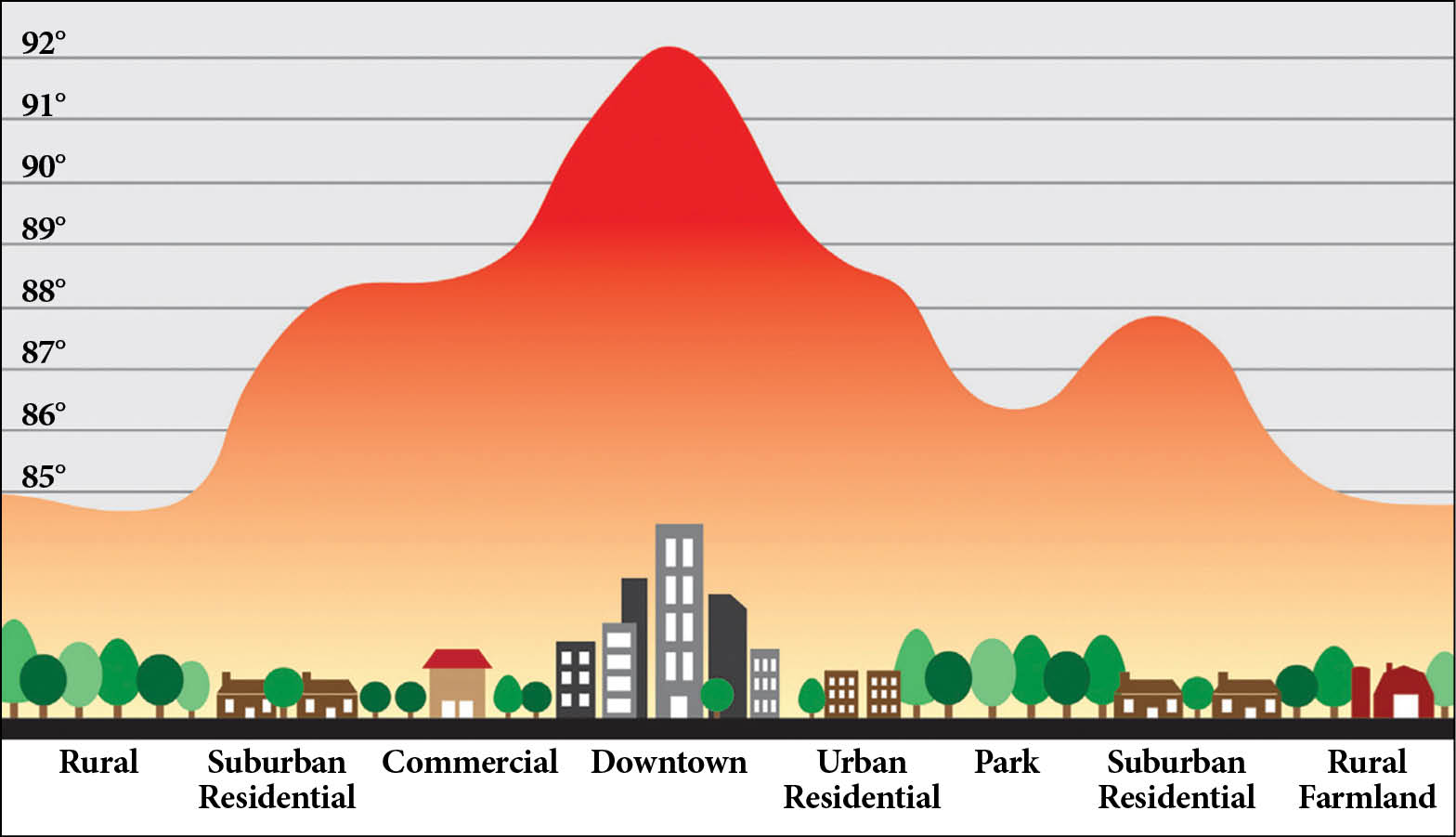

In a phenomenon known as the urban heat island effect, the roofs, streets, and sidewalks in a built-up area absorb heat during the day and re-radiate it, sometimes well into the night, so that heat lingers and accumulates. Building patterns that reduce wind flow, while beneficial during colder seasons, can trap hot air in urban “canyons” and add to the problem.

Excessive heat can have many adverse effects on people and the environment, as evident around the Bay Area during the recent June heat wave. Air quality suffers, as sunlight and radiated heat quickly cook car exhaust into smog. According to the Environmental Protection Agency’s website, “Increased daytime temperatures, reduced nighttime cooling, and higher air pollution levels associated with urban heat islands can affect human health by contributing to general discomfort, respiratory difficulties, heat cramps and exhaustion, non-fatal heat stroke, and heat-related mortality.” In short, all that heat is more than uncomfortable — it’s dangerous. And once it starts to build, it’s difficult and expensive to counteract. Air conditioning helps only inside buildings, while adding to the outdoor temperatures and gobbling electricity.

Climate change may bring even hotter summers to the Bay Area, adding urgency to reducing the heat island effect for the region. Rather than using energy on cooling, more climate-sensitive options look at diminishing the amount of heat that is absorbed in the first place. Experts around the region have been pushing for innovative solutions such as “cool roofs” that reflect sunlight and radiate heat efficiently, “green roofs” planted with vegetation, and parking lots that feature reflective coatings or plenty of shade.

For example, in the recently adopted Clean Air Plan, the Bay Area Air Quality Management District included a proposal to develop and promote a model “cool parking” ordinance to encourage the use of reflective coatings and shade trees when parking lots get built or resurfaced. The plan also includes developing model building codes for cool roofs. These models for parking lots and roofs will also be included as recommended mitigation measures in CEQA comments and guidance to local jurisdictions.

The current version of the state’s CalGreen building codes already includes cool roofs as a voluntary “reach code.” Rachel DiFranco, sustainability coordinator for the City of Fremont, explained that reach codes can be adopted by local jurisdictions to strengthen their building codes. She recounted that when Fremont’s Sustainability Commission considered new reach codes, it chose to add requirements for mandatory solar installations and electric vehicle readiness, rather than cool roofs. “The city really wanted to encourage more solar, and felt that combining solar with cool roof requirements might have been too complex and difficult for some developments,” DiFranco said. However, developers still have the option of cool roofs to achieve additional energy savings for a project.

It’s anticipated that the next CalGreen iteration, due in 2019, will include the cool roof requirements as mandatory code. In San Mateo County, the cities of San Mateo and Brisbane have recently passed ordinances requiring reflective roof materials on low-slope roofs (which have the greatest potential for heat absorption) in both residential and non-residential construction projects. A model cost-effectiveness study has been prepared for various roof types and climate zones by the California Energy Commission’s Codes and Standards Program for cities considering this reach code.

Although green roofs are also included in the CalGreen building codes as a reach code, they are less common than reflective roofs. However, as of January 1, 2017, San Francisco became the first US city to require 15 to 30 percent of roof space to have solar panels and/or vegetation on most new construction. In addition to the landmark domed living roof at the California Academy of Sciences, the city already has a number of smaller green roofs, including the EcoCenter at Heron’s Head Park and the new UCSF Medical Center at Mission Bay. A city-commissioned cost-benefit study concluded that these roofs provide a net benefit to owners; the initial cost is offset by stormwater management savings, while the increased real estate value creates a long-term benefit.

In other parts of the Bay Area where they are not mandated, green roofs can be found on buildings that are constructed according to LEED environmental certification standards or have been designed to generate as much energy as they use. Such projects often also incorporate special pavement types, as at San José’s Environmental Innovation Center, which also includes a cool roof and many other sustainable features.

CalGreen includes voluntary reach codes for both residential and non-residential projects that specify pavement options to reduce the heat island effect of sidewalks, patios, driveways, and parking lots. In addition to permeable (or pervious) pavement, which allows water to pass through or to evaporate slowly from internal pockets, cool pavement options include reflective materials and coatings, grid pavers which allow plants to grow through the spaces, and pavement that is shaded by trees or structures.

A new Pavement Life Cycle Assessment tool for cities to determine the overall life-cycle environmental costs and benefits of various cool pavement options has just been developed for the California Air Resources Board by a team at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s Heat Island Group. Users can weigh the potential for adding to global warming or smog production, generating more particulates, or increasing or reducing energy demands. Co-author Haley Gilbert expects the greatest interest in cool pavement will be in hotter areas like Fresno and Los Angeles, where the study’s tests were run, although that could change in the future as climate change affects northern California. “Some future scenarios were considered, but not future climate,” she explained.

While some reflective materials did not compare well with conventional ones when considering overall life cycle, there are other reasons to require cool pavements. The Heat Island Group research did not include the health benefits of local heat reduction from cooler pavements, which Gilbert observed could be an important component of deciding which options to implement. She also cautioned that the research was focused on how pavement choice would affect average air temperatures city-wide. “We measured at building height, not at street level. The benefit is sometimes downwind, so you could have different effects within individual neighborhoods,” she noted.

Although denser development is often associated with a greater heat island effect, absorbent surfaces in a high-rise area may be smaller than in a suburban business area with many flat roofs and parking lots. Both can benefit from requirements for passive cooling mechanisms, such as reflective or living green surfaces to offset heat build-up and even lower urban temperatures.

Other city ordinances that call for tree planting or parking lot shading may also apply to individual projects. For example, Sacramento has an ordinance that specifies the number of shade trees required for parking lots. Many city and county climate action plans incorporate urban tree planting and other measures to reduce heat islands. At the neighborhood level, parks and other green spaces can also help to offset the impact of heat-absorbing roofs and pavements.

Cities can model best practices to reduce heat, as Menlo Park has done by adding cool roofs to some city buildings. Also, much of the pavement area in cities is publicly owned in the form of streets and sidewalks, so local governments can make their own contribution to reducing heat islands through their public works programs. As Gilbert observed, “Tackling urban heat islands is one local thing that cities can do to offset overall climate change.”

Leslie Stewart covers air quality and energy for the Monitor.